PROJECT 1975

(BARBARIAN & CLASSICS)

The memories are present

Reminders of Difference

2012

In 2003, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization declared Steichen’s exhibition a part of its ‘Memory of the World’ initiative. On its website UNESCO states: ‘While offering infinitely diverse images of human beings living in the 1950s, [‘The Family of Man’] nevertheless emphatically reminds visitors that they all belong to the same big family.’5 It is just this ‘myth of the human “community”’ and the presupposed ‘human essence’ that Roland Barthes criticized in view of the exhibition. ‘Any classic humanism,’ Barthes writes, ‘postulates that in scratching the history of men a little, the relativity of their institutions or the superficial diversity of their skins (but why not ask the parents of Emmet Till, the young Negro assassinated by the Whites what they think of The Great Family of Man?), one very quickly reaches the solid rock of a universal human nature.’6 But without history, Barthes rightly states, ‘there is nothing more to be said about them’. And yet the same applies to Steichen’s exhibition, which is conceptually and historically related to the idea of the museums as an embodiment of, in Tony Bennett’s words, ‘general human universality to which, whether on the basis of the gendered, racial, class or other social patterns of its exclusions and biases, any particular museum display can be held to be inadequate and therefore in need of supplementation.’7

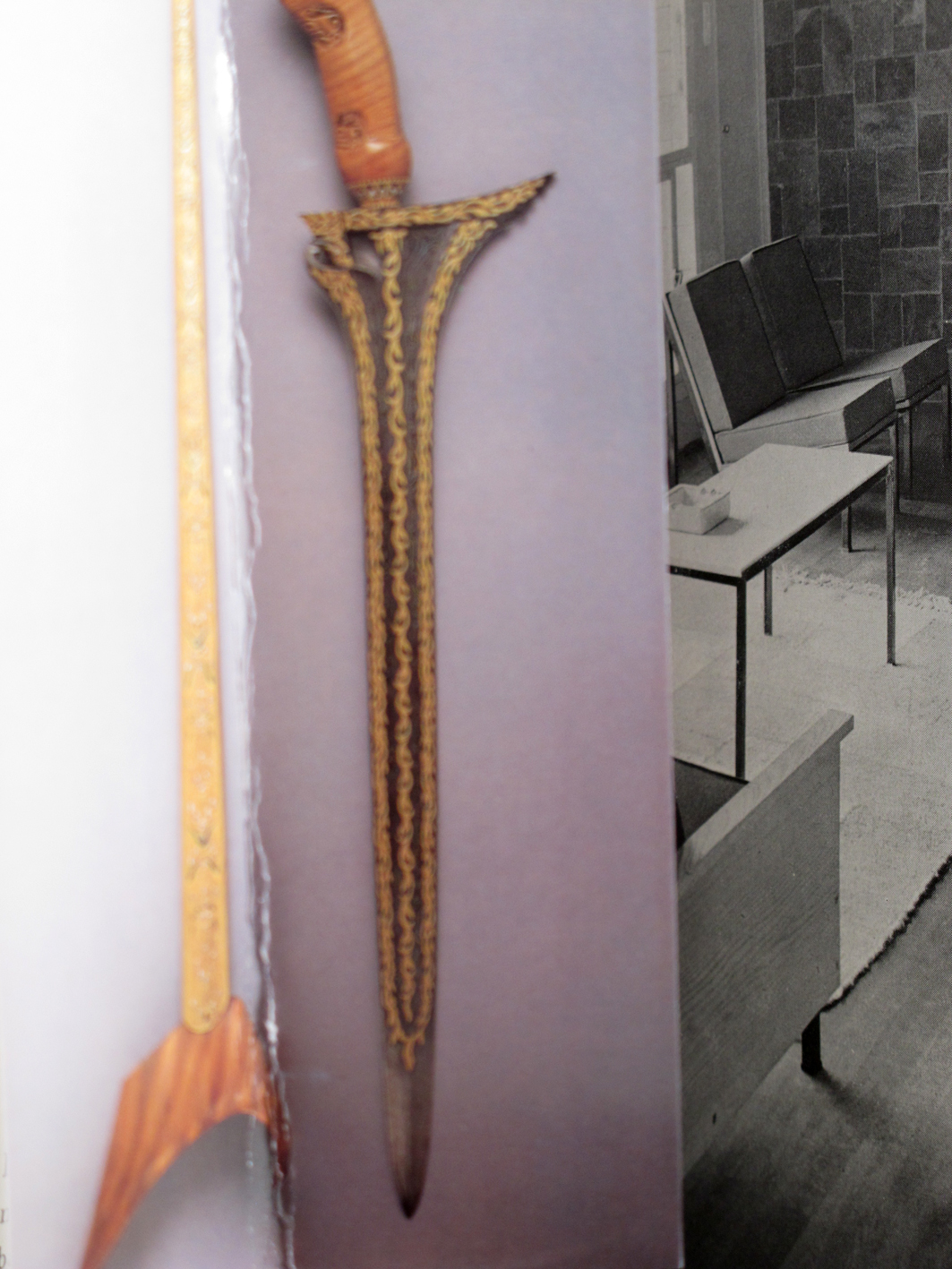

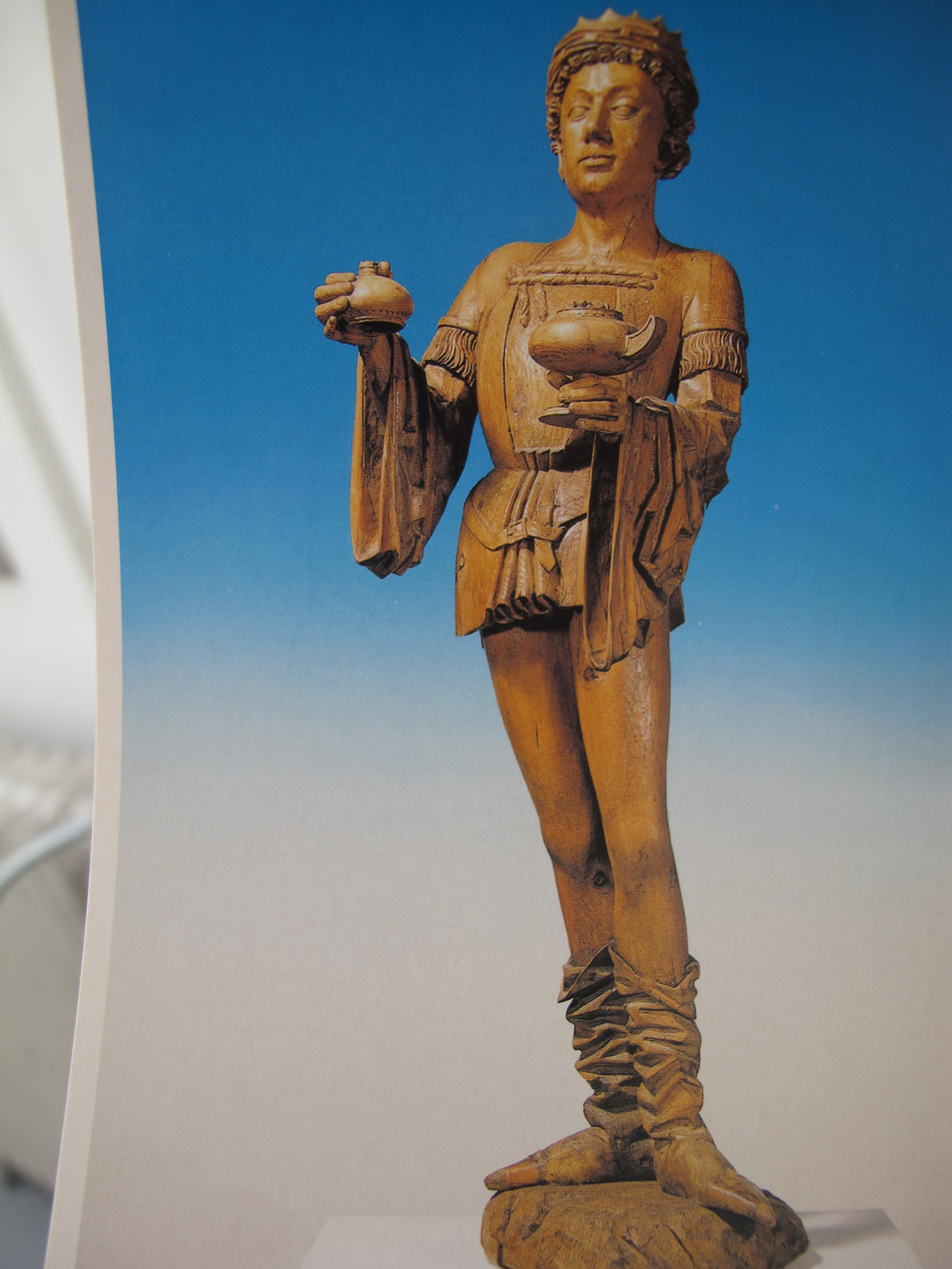

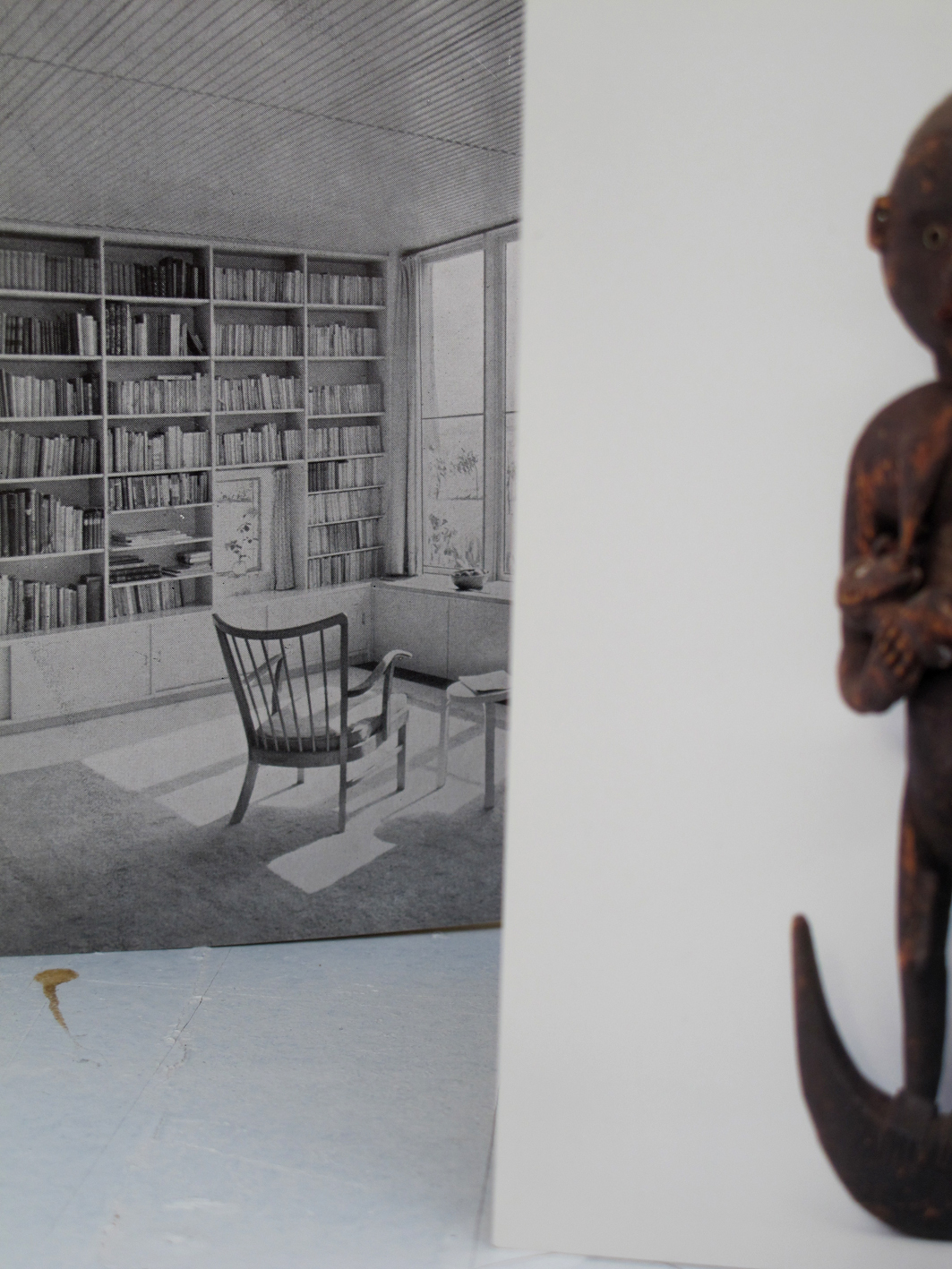

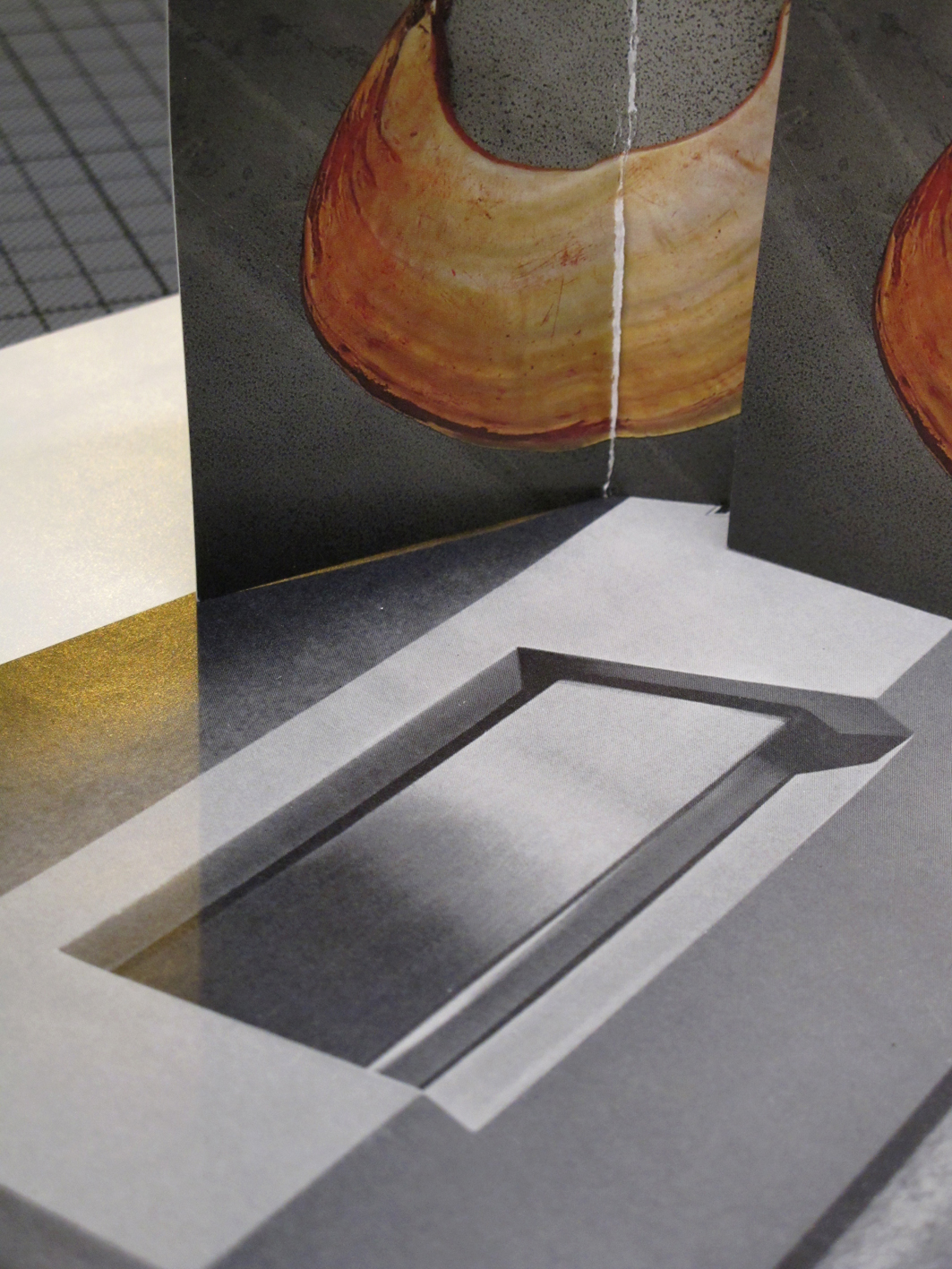

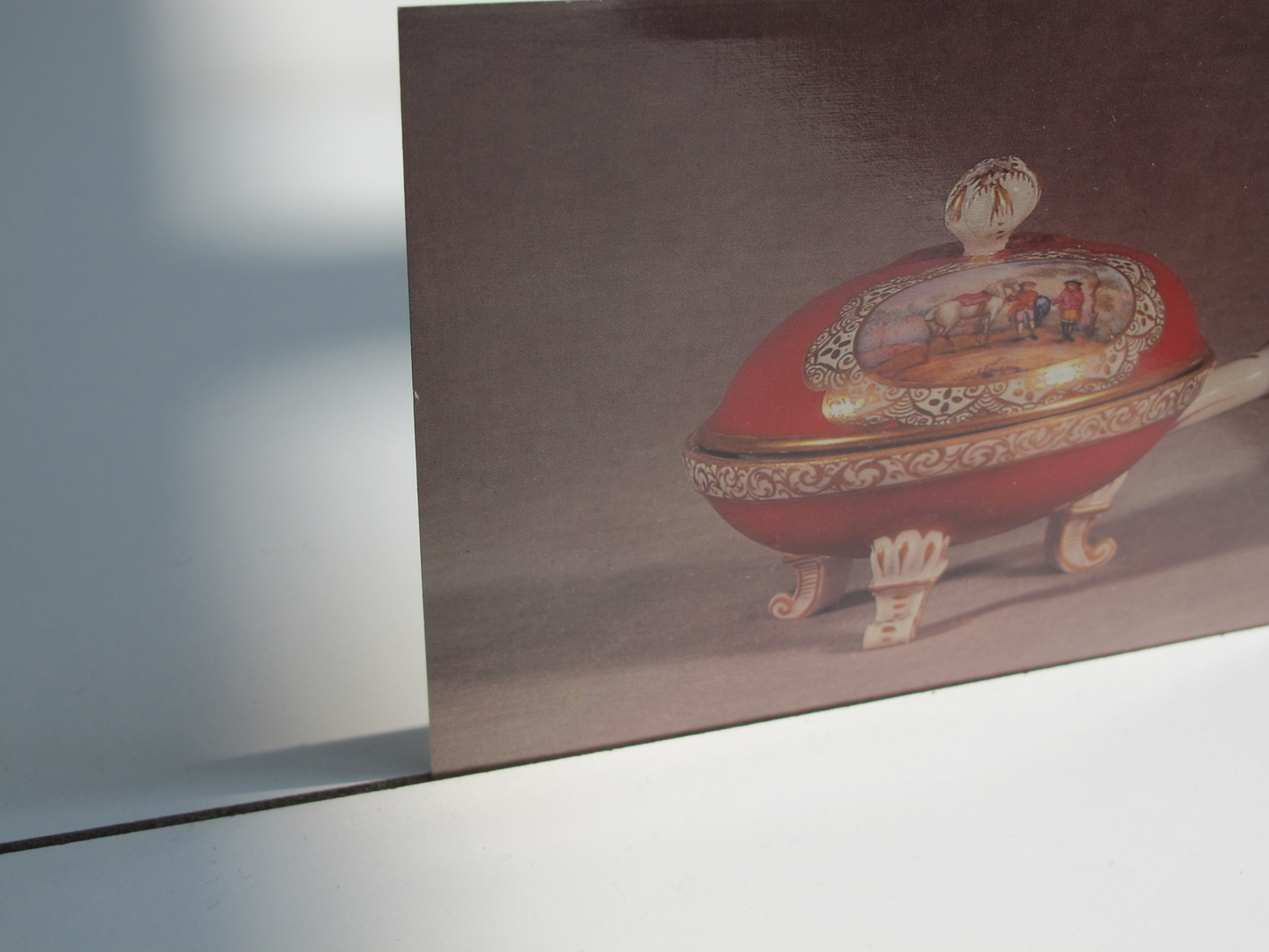

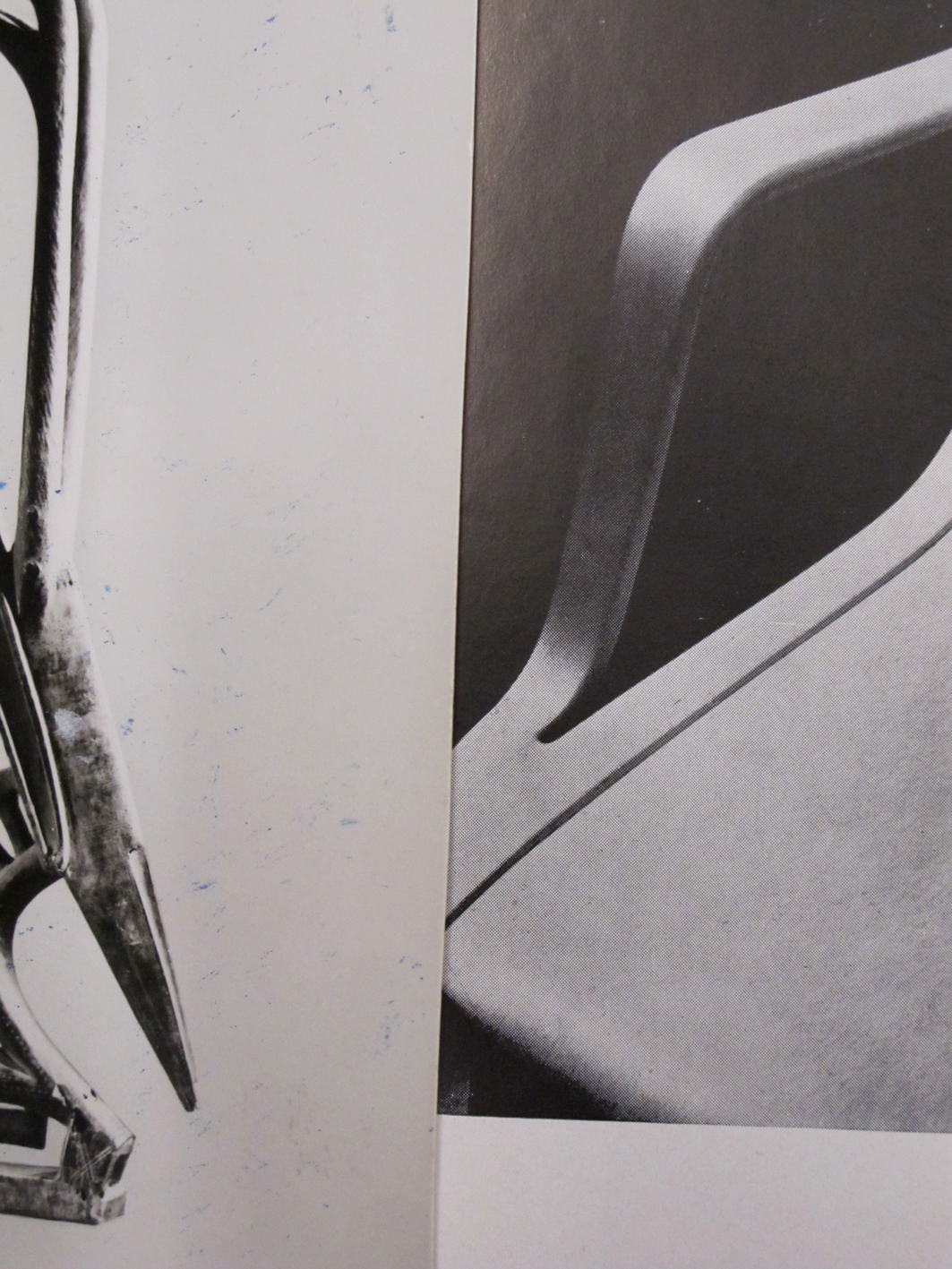

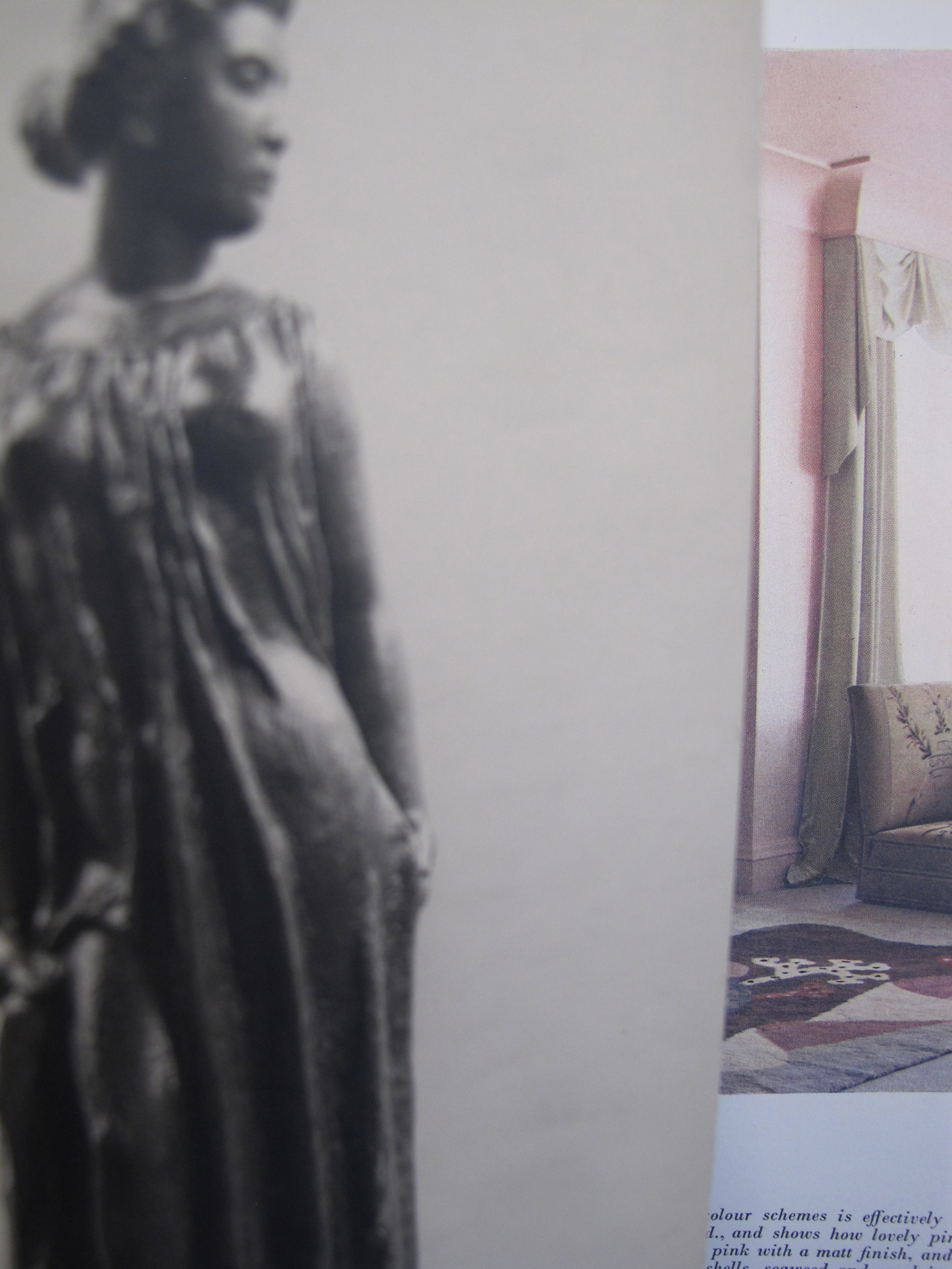

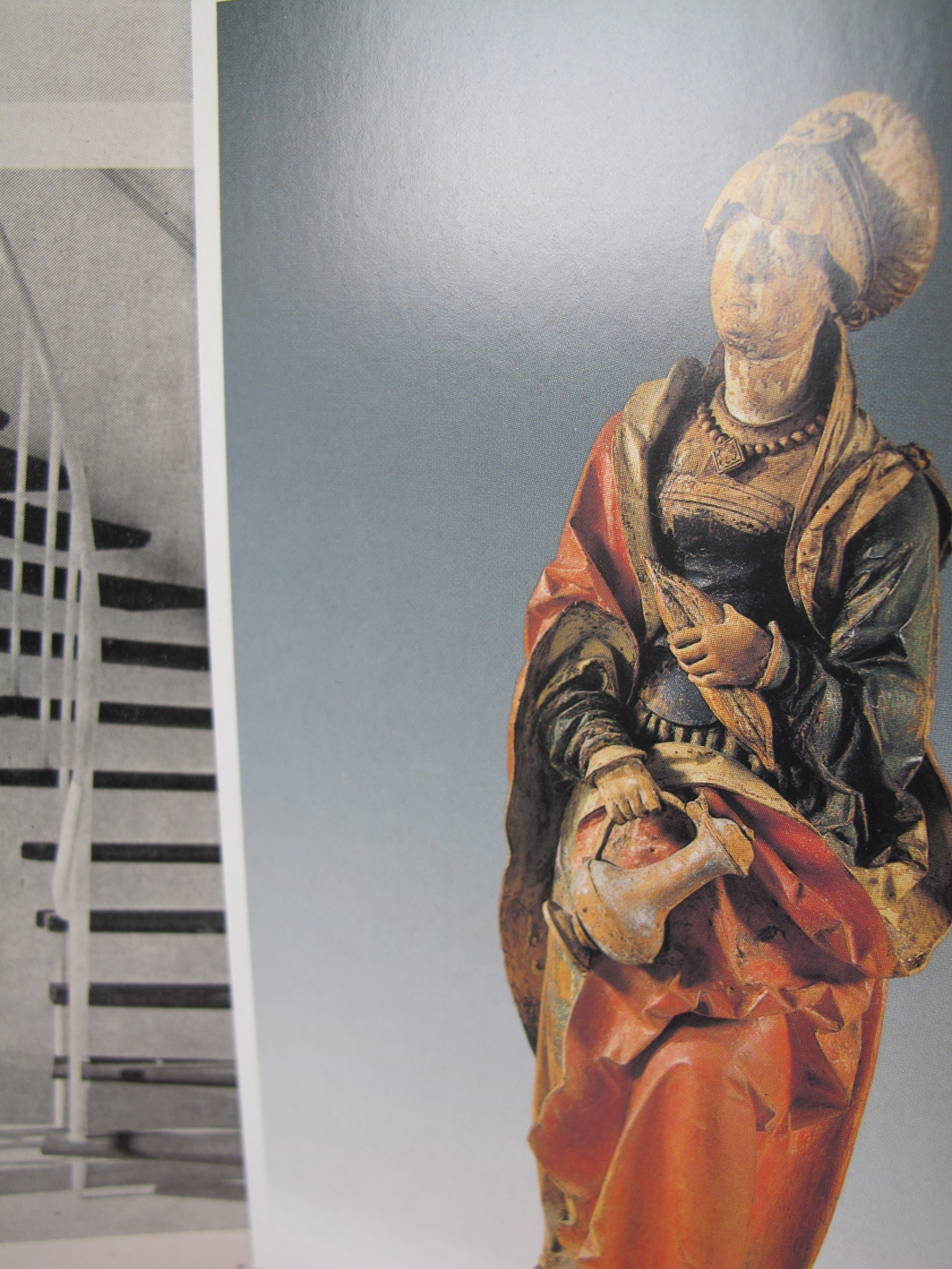

Barbarian & Classics caters to this need for supplementation which, according to Bennett, constitutes an insatiable ‘discourse of reform’. It does so by connecting to the memories handed down to us over time through photography. By quoting Steichen’s exhibition, Westermeier establishes a structural relation to the modernist canon and the universal aspiration that marks the Western conception of modernity. He reforms this universal aspiration by combining (not unlike a world culture museum) significant remains of human cultural achievements made by so-called barbarians with the classics, in just a few square meters. The boundaries that museums drew in the course of time between the barbarian and the classic, or between ethnographic objects and art, are still clearly visible in Westermeier’s photographs; they separate the images of objects taken in different temporal and spatial contexts. By constructing his photographs like modernist collages, which accentuate the fault lines between the combined parts, Westermeier emphasizes difference within the whole, and the fact that a museum and its exhibitions cannot be like ‘a solid rock of a universal human nature’, because this would mean it would get out of touch with the changing society in which it is embedded.

Kerstin Winking, 2012

Taken from SMBA Newsletter 128,

THE MEMORIES ARE PRESENT

Artun Alaska Arasli, Pauline M’barek, Christoph Westermeier,

Stedelijk Museum Bureau Amsterdam, June 16-August 12, 2012

smba project 1975 (BARBARIAN & CLASSICS)

double side mounted images, 84x63 cm, 84x112 cm and 92x69 cm, 2012

Installation view SMBA, Amsterdam, Photo Gj. Van Rooij

Recent