KÖRPERLICHE ERTÜCHTIGUNG

2017

Christoph: Jonas, we spent the past September and October in Moscow, where we both read Werner Herzog’s Of Walking In Ice — a book that doesn’t really have anything to do with Moscow or Russia’s history but rather catalogues a young filmmaker’s travels through Southwest Germany. During the seventies, Herzog made a journey from Munich to Paris on foot in order to visit the heavily ill Lotte Eisner. His logs read like a journey of self-discovery. Herzog describes his thoughts and experiences, and how they come about while walking. Reality and fiction dissolve into each other, and you can participate in the emergence of thoughts. The book became a shared point of reference for both of us since we both decided independently of each other to acquire our experiences of Moscow through walking.

Jonas: Werner Herzog was our age at the time. The book was like a blueprint or guide for how we could move through the landscape of Moscow. It was a similar setting: we didn't have any specifications or appointments that would determine how we structured our time. We moved impartially across foreign territory and tried to use our senses, perceptions and inner monologues to try to arrive in Moscow.

Christoph: Werner Herzog writes about loneliness in a positive sense. In Moscow I also ex-perienced loneliness as something positive.

Jonas: Without knowing it, I was expecting to have the luxury of loneliness in Moscow, the luxury of leaving the social context for a period of time, and that’s exactly what Herzog de-scribes. It wasn’t about having fun.

Christoph: Herzog describes a process of self-discovery. He became newly acquainted with himself and his thoughts through walking. He would walk through areas that were simultane-ously familiar yet foreign. I experienced something similar in Moscow, though under entirely different conditions. Herzog was walking through the countryside whereas we were walking through a mega-city.

Jonas: Which observations did you make while walking?

Christoph: I developed a different feeling for architecture. Moscow comes across like any fa-miliar European city at first. But small discrepancies start to emerge quickly, and you start to get the feeling that this seemingly familiar vocabulary is being read in a different way. Mos-cow looks like a European city but it isn’t one. It isn’t an Asian metropolis either. Moscow is Moscow.

Jonas: I also experienced the same. It wasn’t like an East Asian city with food stalls and flashing neon signs and the like. There wasn’t any of that. It was an experience of a different kind of order, an omission of things. A lot of those complex layers that we use to come to terms with the public spaces of German streets just didn’t apply there. It was extremely fas-cinating, and it made walking through public space so attractive. I could look at the architec-ture in such an unhampered way, unfamiliar to those of us from Germany. Of course we’re biased: you aren’t in the position the look around impartially in the places you know well. And even when you return and want to use this newly learned gaze here, it doesn’t work the same way as it does there. That was thrilling. And of course it was also a different form of experiencing the presence of gigantic urban planning. It’s crazy. Coming from German cities, you’re just not used to permanently experiencing views laid out by urban planning from sixty, seventy years ago that remain present in the same form in the here and now.

Christoph: Was it easy for you to record these views photographically?

Jonas: I felt like they lent themselves to it. Taking photos there felt attractive since many of the buildings were so exposed. Some problems don’t even come up like “there’s advertising in the way, and it’s blocking the essential features…” It makes the realization simpler. You can see that they’re buildings that embody a different time, a different spirit while still having the absurd presence of 2016. Of course, you can say that there are also old buildings in Ger-many that also point to times past, but I think this appears heterogenous and indistinct in a different way than it did in Moscow.

But you were also dealing with some aspects of historical architecture weren’t you?

Christoph: Historical architecture is always connected with a question mark. What’s been renovated and how has it been restored; where and how does an idea of ‘the historical’ inter-vene? In Moscow, there’s a lot of construction and renovation underway. The construction sites are shrouded in plastic sheeting with images of historical buildings printed on it. Reali-ties blur, and the temporary imitation of a building becomes a reality of its own framed in ivy. They’re Potemkin villages for the twenty-first century.

Jonas: It’s not entirely clear if one can expect restoration work there in any traditional sense, or if it’s rather an issue of medium-term permanent solutions in which the buildings are opti-cally adjusted to fit each other, constructing a sort cohesive and closed core of the city. We also experienced that Stalin-era buildings are very present in the city. And even with more recent buildings, one can still recognize a somewhat neo-Stalinist style; I think it’s called the ‘Moscow Style.’

Christoph: The history of Moscow’s architecture shows how Constructivism developed after the October Revolution in 1917 within the context of a society that was reorienting itself. People believed in a historical rupture and found a new architectonic language for it. Rod-chenko, Melnikov and others were building spaces for a new society. Stalin followed Lenin, and after a relatively open, early period of Stalin’s rule, harsh totalitarian Stalinism began in the thirties, which entailed unimaginable acts of cruelty. This had nothing to do with early Leninism and the optimistic atmosphere of the revolutionary years anymore. It was a funda-mental inversion. Politically, socially and culturally, there was an about-face, and everything had been exchanged by the end. Clear-cut Constructivism was followed by an opulent and baroque Stalinism. The gingerbread style of Socialist Classicism, which isn’t valued at much in contemporary aesthetic debates, was nonetheless something of a positive surprise for me.

Jonas: The Stalinist architecture also overwhelmed me. I was expecting to engage more with Constructivism in Moscow and assumed that it would be the most aesthetically stimulating for me. But the most present buildings I noticed were in this gingerbread style, and I was fasci-nated by their charisma — a presence from the thirties to fifties that dominated the cityscape, probably as much now as it did then. It’s not really clear what’s being expressed: the Gothic, verticality, striving to the heavens…

Christoph: The Baroque, the ornamental…

Jonas: It’s pure eclecticism; there’s nothing rational about it. One suspects some kind of competition with the Americans and feels constantly reminded of the Empire State Building or the Chrysler Building. Of course, those buildings demarcated a certain territory, and a lot of architects rubbed up against its boundaries, but I was surprised to find so many references in Moscow. Today, you can’t just apply this aesthetic form so uncritically, but it’s still fascinat-ing. It’s present, and you can understand that the Moscow Style of the late nineties should be described as post-stalinist.

Christoph: As a tourist, you move through the city differently than a resident. We were in Moscow for two months, a period longer than a tourist’s vacation, but we also weren’t resi-dents of the city.

In the 1920’s, young European writers were invited by the young Soviet Union to experience the establishment of Communism first hand. They would spend two months in Moscow, and the journals of Walter Benjamin and Egon Erwin Kisch still offer a lively image of those times. Since we were going to spend the same period of time in Moscow, I wanted to flirt with this tradition of cultural exchange. It wasn’t just about finding a way to scratch the surface, but also about gaining some insight, and you end up in an intermediate stage. You dive in but don’t lose the overview. You don’t become a part of things, but you also aren’t totally left out. You’re in a special position to experience friction and exchange without getting lost in a dif-ferent culture.

Jonas: That’s exactly what I took with me. I didn’t take on a second identity, and I’m not a half-Russian now that knows Moscow like the back of my hand. But I could look at things at great length and in great detail, and discover many exciting things that are still bubbling and brewing inside of me. As a tourist, you’re scratching so much at the surface that you spend more time testing prefabricated ideas, doing the rounds, confirming cliches, checking things off the list than you originally intended to. We didn’t have to get anything done and, as for-eigners, had time to let these confrontations affect us over two months.

What do you plan to do with your experiences, these themes?

Christoph: In the tradition of the tradition-steeped cultural exchange between East and West, we could explore Moscow as flâneurs. We acquired our experiences of the city through walk-ing in a completely individual manner. Open and unbiased, we undertook our journeys through the city. This open view changed both of our perceptions of city, state and society. This unleashed a lot of things for me and the process isn’t yet complete. We both experi-enced the city on the move, and I want to continue these wanderings by flâneuring through my image archive.

Jonas: I feel a certain tension that I won’t be able to do these walks anymore, and that leads to me having to repeat them in my imagination. It’s something like a digestive process. What’ll come out of this still remains unclear. That’s in line with my working process. I collect material, or eventually appropriate it, and then I can’t view it at a distance anymore. I need to develop a certain distance, and this distance then serves to check things and compare them with the immediacies we experienced in Moscow. During our stay there, we reacted to the situation with the exhibition Walkers at the Rodchenko School. Now we’ve developed differ-ent perspectives.

Jonas Gerhard and Christoph Westermeier, 2017

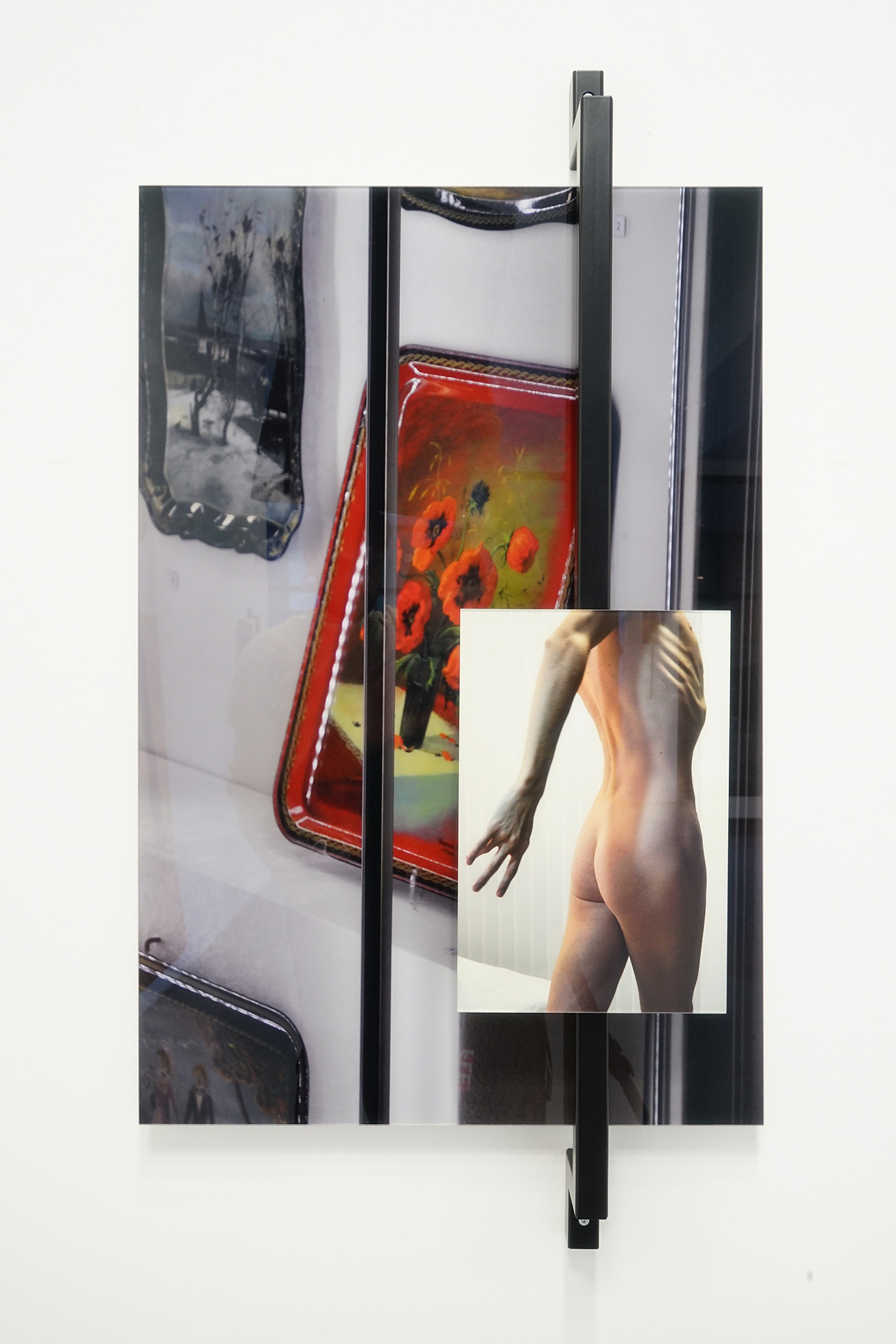

KÖRPERLICHE ERTÜCHTIGUNG

Mixed Media Installation, 2016/17

Installation view "To Wander at Large" with Jonas Gerhard, Atelier am Eck, Düsseldorf 2017

Recent